Afraid of being afraid?

The year was 2008. An election year. The month was November when California voters cast their ballots for candidates including state and federal initiatives. At the time, Proposition 8 was the most emotional and controversial initiative on the ballot. Below is its definition:

Proposition 8 consisted of two sections. Its full text was:[34]

SECTION 1. Title

This measure shall be known and may be cited as the “California Marriage Protection Act.”

SECTION 2. Article I, Section 7.5 is added to the California Constitution, to read:

Sec. 7.5. Only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California.

Latter-day Saint Church leaders encouraged California members to engage in the political process by donating money in support of the initiative, posting “Support Prop. 8” signs in our yards, bumper stickers on our cars, setting up phone trees, walking precincts, and standing on street corners waving signs. Understandably, many Church members (myself included) felt conflicted—especially those of us living in the deeply progressive San Francisco Bay Area. Rightly or wrongly, a lot of us felt conflicted on two levels: 1) The sensitive nature surrounding the issue of same-sex marriage 2) The Church’s involvement in the political process. (As we know, Latter-day Saints are still divided over same-sex marriage and/or other LGBTQIA* issues.)

Meanwhile, my place of employment (my local university) pressed employees to fight against Prop. 8. After 15 years of teaching at this university, I was well-versed in the policies and politics involving “Diversity, Equity, Inclusion” (called DEI) coupled with its growing influence and power within North American universities, institutions, and culture.

As a form of protest against Prop. 8, my university department designed t-shirts with the slogan, “No on Prop Hate” for staff and faculty to buy/wear as “representatives against hate and inequality.” My department also encouraged us to protest the nearby Marriott Hotel because Latter-day Saint, Willard Marriott, owned the hotel chain. The department head also sent an email offering help for employee donations to the “No On Prop Hate” campaign. Finally, university faculty were encouraged to post “No on Prop Hate” signs on office doors.

The meme below was broadly circulated online among California LDS church members.

A popular meme taken from Arnold Friberg’s painting of the Book of Mormon’s Samuel the Lamanite

Not surprisingly, public fall-out from the Church’s support of Prop. 8 grew increasingly contentious. “Anti-Mormon” protesters chanted and taunted Prop. 8 supporters in the streets, on the grounds of some LDS church buildings, and in front of the Los Angeles and Oakland temples. Other protestors scrawled hateful messages on some LDS church buildings and on some of the outside walls of at least one California temple. Protestors threatened to storm Sacrament meetings. Some burned Prop. 8 signs on LDS church grounds. Local newspapers criticized the Church and its members for helping to fund Prop. 8. Worst of all, Latter-day Saints who had donated money to Prop. 8 were doxxed online. Their home addresses, their places of employment, and their donation amounts were publicly exposed for purposes of shaming and punishment. Businesses and business owners who had donated were also exposed and shamed.

As a blogger, I have tried to avoid political advocacy or controversy. And, I have never criticized The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; I don’t intend to criticize it now. Having said that, I will be honest: rightly or wrongly, my fear, anxiety, and resentment heightened during this painful time. I was tired of feeling pressured by my place of employment and my place of worship to publicly “pick a side.” Along with that, many of my university colleagues knew I was a Latter-day Saint; several of my colleagues were gay and lesbian and my personal friends. My position as an adjunct college instructor was not shielded by tenure, so I hoped my superiors and colleagues would act in good faith toward me (which they did).

In any case, and for the first time in my life, I felt real fear and anxiety due to my membership in the Church. (As of this writing, the Church and Prop. 8 are still negatively connected here in the Bay Area.) Regardless, I will always publicly and privately stand with the Church. This idea sounds simple enough. However, in 21st century North America, DEI’s ever expanding edicts, admonitions, and punishments for non-compliance have instilled an environment of anxiety and a fear of “being cancelled” in workplaces and in the broader culture.

During that 2008 November evening while driving home from work, I feeling afraid. Again. I began to pray. Again. I pleaded with God for strength, for courage, for guidance, for utterance. What should I think? What stance should I take? I prayed for wisdom to know if or when to open my mouth—and when to shut it. As always, God spoke peace to my heart; the familiar verses from the Doctrine and Covenants, Section 121 came to mind:

Peace be unto thy soul; thine adversity and thine afflictions shall be but a small moment. And then if thou endure it well, God shall exalt thee on high; thou shalt triumph over all thy foes. Thy friends do stand by thee, and they shall hail thee again with warm hearts and friendly hands….thy friends do not contend against thee…

God also reminded me that despite the social and political turmoil, I was living in peace. No one was threatening my life or my family, or burning down my home, or forcing me to leave town. I wasn’t dealing with or hiding from violent and relentless persecutors that early Latter-day Saints endured.

Looking back, my fear and anxiety were partly rooted in a sort of pseudo fear that can be mistaken for genuine fear. Yes, I was afraid. But, I was also afraid of being afraid. Too often (regardless of who we are or with which group we belong), we forget how our perception can become distorted toward perceived opponents along with people who have authoritative power over us. In our fear, we tend to give opponents and “powerful” people more power or authority than they actually have. Consequently, we might perceive them as larger and more ominous than they really are. Adding to our fear, opponents can (and often do) emanate a false bravado or facade to intimidate and gain our compliance.

In my previous post, I highlighted Malcolm Gladwell’s book, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits and the Art of Battling Giants. Gladwell’s research can help lessen our fears. For instance, consider his claims:

Giants are not what we think they are. The same qualities that appear to give them strength are often the sources of great weakness (Introduction, p. 6).

There is an important lesson in all battles with giants. The powerful and the strong are not always what they seem (Introduction, p. 14).

Thus, what looks to be our opponent’s advantage might actually be to our advantage. Gladwell further claims that this distorted and disproportional fear—coupled with distorted perceptions about our disadvantages—undermines our ability to fight. He writes:

We are often misled about the nature of advantages. Now, it is time to turn our attention to the other side of the ledger. What do we mean when we call something a disadvantage? Conventional wisdom holds that a disadvantage is something that ought to be avoided—that it is a setback or a difficulty that leaves you worse off than you would be otherwise. But that is not always the case. I want to explore the idea that there are such things as ‘desirable difficulties.’ [Thus] when people see themselves at a disadvantage, they’ll use more resources…and they’ll process more deeply or think more carefully about what’s going on. If they have to overcome a hurdle, they’ll overcome it better when you force them to think a little harder. Difficulty turned out to be desirable. There are times and places where struggles have the opposite effect—where what seems like the kind of obstacle that ought to cripple an underdog’s chances is actually [a variable for a better outcome]“

(p. 100, 105).

Furthermore, our compensating mechanisms “requires that [we] confront our limitations and overcome [our] insecurity and humiliation” (p. 112). In other words, we can confront fear, experience fear, and redefine fear in order to overcome fear. Jesus Christ repeatedly taught this same principle in the New Testament. For example, we read about the wealthy young man who sought to be a disciple of Christ. Here, Christ tries to teach about the “disadvantage of advantage” along with distorted or false notions of power. Christ tells the young man, “If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell all that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven, and come and follow me. When the young man heard that saying, and he went away sorrowful for he had great possessions” (Matthew 19: 21-22). We see how this young man’s fear of losing his advantages/security causes him to forfeit or “lose” the ultimate advantage and freedom: the companionship and the teachings of the Savior of the World. The youth’s obvious economic advantage becomes a disadvantage. Christ’s temporal poverty compared to the young man’s wealth looks disadvantageous, but in reality, is the ultimate treasure.

“Christ and the Rich Young Man” by Heinrich Hofmann

In furthering his points, Gladwell illustrates the courage of British citizens who faced Germany’s blitzkrieg against England during WWII. Anticipating the destruction of German bombs on British cities, England’s government officials built psychiatric hospitals around London to help traumatized citizens. Surprisingly, most Londoners learned to overcome their “fear of disadvantage” as compared to the German bomber planes and the Nazi’s overall power to obliterate England. Gladwell explains:

In the fall of 1940, the long-anticipated attack began. Over a period of eight months—beginning with 57 consecutive nights of devastating bombardment—German bombers thundered across the skies above London, dropping tens of thousands of high-explosive bombs and more than a million incendiary devices. Forty thousand people were killed, and another forty-six thousand were injured. A million buildings were damaged or destroyed. In the city’s East End, entire neighborhoods were laid waste. It was everything the British government officials had feared—except that everyone of their predictions about how Londoners would react turned out to be wrong. The panic never came. The psychiatric hospitals built on the outskirts of London were switched over to military use because [none of the citizens] showed up [in need of psychiatric care]. As the Blitz continued, as the German assaults grew heavier and heavier the British authorities began to observe—to their astonishment—not just courage in the face of the bombing but something closer to indifference. [Another] thing that soon became clear was that it wasn’t just the British who behaved this way. Civilians from other countries also turned out to be unexpectedly resilient in the face of bombing. Bombing, it became clear, didn’t have the effect that everyone had thought it would have (p. 128).

Gladwell details this amazing mentality in quoting psychiatrist J.T. MacCurdy:

We are prone to be afraid of being afraid, and the conquering of fear produces exhilaration… When we have been afraid that we may panic in an air-raid, and, when it has happened, we have exhibited to others nothing but a calm exterior and we are now safe, the contrast between the previous apprehension and the present relief and feeling of security promotes a self-confidence that is the very father and mother of courage“

(p. 133).

We see this phenomenon time and again in the scriptures: Joseph in the Old Testament thrived as a disadvantaged slave. David, as a disadvantaged shepherd boy, thrived in his battle with advantaged Goliath. The Prophet Joseph Smith (much like the the original apostles) grew so accustomed to disadvantage and persecution that he became emotionally unencumbered by it. In other words, like a vaccine, the hardships and persecutions inoculated Joseph Smith against the disease (or disadvantage) of the “fear of persecution.” He persevered and completed his work. He thrived rather than succumbing to paralyzing fear. Knowing he would soon be martyred “as a lamb to the slaughter,” the Prophet Joseph willingly put himself in enemy at Carthage Jail, but “felt as calm as a summer’s day.”

“Against the Christian Door” by Andre Knaupp

Gladwell further advises:

We underestimate how much freedom there can be in what looks like a disadvantage [for us] (p. 91). The idea of desirable difficulty suggests that not all difficulties are negative. Being a poor reader (dyslexia) is a real obstacle, unless….that obstacle turns you into an extraordinary listener, or unless….that obstacle gives you the courage to take chances you would never otherwise have taken. Too often, we make the same mistake as the British [governmental officials] did and jump to the conclusion that there is only one kind of response to something terrible and traumatic. There isn’t. There are two“

(p. 133).

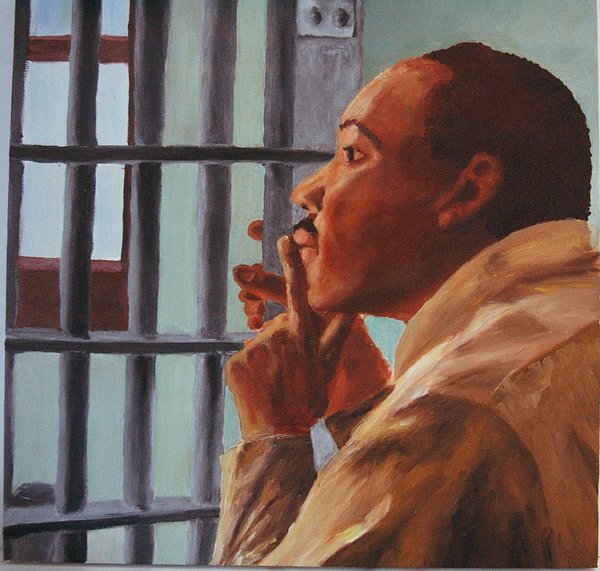

Before his martyrdom, Martin Luther King, Jr. welcomed his time spent in jail. Turning a disadvantage into an advantage, he remarked, “Jail helps you to rise above the miasma of everyday life. I catch up on my reading every time I go to jail” (p. 186). Encouraging civil rights leaders to adopt the same mindset, King advised them to be unafraid of arrest and incarceration and to embrace it as a strategical opportunity. He told them, “The only way we are going to save the people is we who are the leadership have to give ourselves up to the mob” (p. 174). We, too, can thrive under extreme disadvantage. During WWII, President Franklin D. Roosevelt strengthened American resolve saying, “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.” (I think I’m beginning to understand this concept.)

Artist: David Lee Solderlind

Gladwell again defers to MacCurdy’s teachings:

We are all of us not merely liable to fear, we are also prone to be afraid of being afraid. Because no one in England had been bombed before, Londoners assumed the experience would be terrifying. What frightened them was their prediction about how they would feel once the bombing started. Then German bombs dropped like hail for months and months, and millions of remote misses (people who lived in close proximity to bombed neighborhoods) who had predicted that they would be terrified of bombing came to understand that their fears were overblown. They were fine. And what happened then? Again, the conquering of fear produces exhilaration. Courage is not something that you already have that makes you brave when the tough times start. Courage is what you earn when you’ve been through the tough times and you discover they aren’t so tough after all. Do you see the catastrophic error that the Germans made? They bombed London because they thought that the trauma associated with the Blitz would destroy the courage of the British people. In fact, they did the opposite. It created a city of remote misses, who were more courageous than they had ever been before. The Germans would have been better off not bombing London at all“

(p. 147).

Gladwell closes his book with this thought:

There are real limits to what evil and misfortune can accomplish. If you take away the gift of reading, you create the gift of listening. If you bomb a city, you leave behind death and destruction. But you create a community of remote misses. If you take away a mother or a father, you cause suffering and despair. But one time in ten, out of that despair rises an indomitable force. You see the giant and the shepherd in the Valley of Elah and your eye is drawn to the man with the sword and shield and the glittering armor. But so much of what is beautiful and valuable in the world comes from the shepherd, who has more strength and purpose than we ever imagine“

(p. 274).

The prophets have warned us of increasingly difficult times ahead. The Apostles Paul and Peter learned to “rejoice” in oppositional opportunities and persecution. Modern-day prophets tell us to prepare and to brace ourselves—while assuring that we can live unencumbered and unafraid as Christ’s Second Coming draws nearer.

Fresh courage take,

Julie