Peace at any price is no peace at all.

As the middle child in my family for the first eight years of my life, I got pretty adept at peacekeeping—I simply stayed out of the fights between my older and younger siblings. Very typical for middle children; they are often considered the more quiet, passive, low-profile kids. Sometimes, my mother called me a “peacemaker.” So, I beamed when my Sunday School teachers quoted Christ’s Beatitude, “Blessed are the peacemakers for they shall be called children of God” (Matt. 5:9). Over the years, I’ve worked hard to “keep the peace”—often at the expense of my own feelings and my own sense of integrity. I eventually came to realize that peacemaking and peacekeeping are two very different ideals—and that conflict avoidance and keeping the peace are not necessarily forms of peacemaking.

I’ve also grown to understand how my own unhealthy “peace at any price” or peacekeeping mindset contributed to some of my less than healthy friendships/relationships. For example, as a young married woman, I was in an unhealthy friendship with a woman who often “teased” me by putting me down. I went along with it (and responded with passive-aggression) because I didn’t know how to respond in emotional healthy ways. Looking back, I also felt a certain “righteousness” at supposedly “turning the other cheek.” My “powerlessness” and methods of “peacekeeping” subconsciously gave me a temporarily false sense of power and a false sense of righteousness. Still, I felt like her “emotional hostage” after a period of time whenever I interacted with her. As I came to understand my feelings toward her and our “friendship,” I was able to extricate myself from this unhealthy dynamic. I had learned to see that my own complicity in our unhealthy interactions; my “peacekeeping” tactics of remaining silent when she put me down coupled with my passive-aggression toward her, not only allowed but encouraged this negative relationship. Later on, I earned a graduate degree in communication studies that further taught me peacemaking skills rather than reliance on failed peacekeeping tactics.

“The Peacemakers” by George Healy

Rod Smith is a relationship expert and newspaper columnist. I particularly liked one of his columns entitled, “Peacekeeping/Peacemaking—There Is a Difference.” I’ve mentioned in previous posts that we can individually and collectively remove our “all is well” or peackeeping “masks.” It takes guts and self-examination to do this, but our reward is attaining true peace within ourselves, our interpersonal relationships, and ultimately, authentic peace within our Church community. Dr. Smith underscores this idea:

- There is a big difference between keeping peace (peacekeeping) and making peace (peacemaking). In a troubled emotional environment peacekeeping takes a lot of work, saps energy, and is usually a never-ending task. Peacemaking lays groundwork for authentic peace to rule.

- Peacekeepers work hard to keep the tensions from rising. They work hard at pretending that nothing is wrong and nothing is bothering them. Jesus was a peacemaker and He calls his followers to be peacemakers. Peacemakers allow tensions to surface, even encouraging tensions to be aired. They might even precipitate conflict. Peacekeepers avoid conflict at any cost. Their reward is the semblance of peace and tranquility and the slow demise of their integrity.

- Peacemakers invite necessary conflict because they know there is no other pathway to increasing of understanding between warring people and groups.

- Peacekeepers can endure fake peace for decades while the tensions erode at their well being and it often leads to feelings of being “called” or anointed. Peacekeepers often have high levels of martyrdom. How else would they rationalize the stress that accompanies the effort of trying to hide the proverbial elephant in the room? Peacekeepers are often portrayed as deeply spiritual because they can endure so much without “saying anything.” They often see their suffering, not as an expression of being misguided or of stupidity, but as a product of faithfulness to being Christian.

- Peacemakers value authentic peace more than its distorted parody. The peace that exists between people with the courage to endure conflict, for the sake of lasting peace, is like gold when compared with its counterfeit cousin. In your family, at your work place, at your place of worship, move toward lasting peace with courage. Assume your legitimate role as a peacemaker rather than avoid conflict in order to keep a semblance of peace that is not worth having (Smith, “Difficult Relationships,” Feb. 2, 2006).

Interestingly, one of Smith’s readers commented on this particular column saying, “‘Appease’ ment’ is the main activity of ‘peasekeepers.’ A distinction should be made between ‘peace’ and ‘pease.'”

“Good Neighbors” by John William Waterhouse

I admire Jeff Von Vonderen, a counselor and interventionist on the television show Intervention. He’s also a pastor and gives valuable advice to the Christian community:

Peace and unity are important in the body of Christ. But experiencing true peace and unity does not mean pretending to get along or acting like we agree when we don’t. [Some scriptural] versus have been used to get people to act unified when they are not. The result is a ‘can’t talk’ relationship system in which problems get swept under the carpet. Because people are not really unified at all, dissensions and strife grow through gossip and backstabbing. In order to protect peace and unity they have to already exist. It is not possible to preserve or maintain something that is not there. In a spiritually abusive [and emotionally abusive] system, people are taught how to counterfeit peace and unity. The irony is that what is actually maintained is a lack of peace and unity.

From the field of counseling, we draw in the concept of the person in a dysfunctional family system who keeps or enforces a false peace, a person know as the ‘peace-keeper.’ This is the person in a relationship system who gets in the middle of everyone else’s relationships and tries to help them ignore their problems with one another. A true peacemaker, as noted in Matthew 5 (of the New Testament), is someone who goes where there is no peace and makes peace. It is not someone who covers over disagreement with a cloak of false peace. It is not someone who gets people who are in total disagreement to act as if they are on the same side. For real peace to happen, not just a cease-fire, there has to be a change of heart. It takes just as much energy to not deal with problems as to deal with them. Actually it takes more energy—because in not dealing with problems, you get to keep the problem plus, you have to work hard to cover it up“

“The Subtle Power of Spiritual Abuse,” pp. 90-91

In my previous post, I wrote about the pseudo spirituality of the Pharisees. This concept is also applicable to the many Church discussions regarding Jesus Christ and the fig tree. The Book of Mark in the New Testament gives the following account:

And on the morrow, when they were come from Bethany, He was hungry. And seeing a fig tree afar off having leaves, he came, if haply he might find any thing thereon: and when he came to it, he found nothing but leaves; And Jesus answered and said unto it, ‘No man eat fruit of thee hereafter for ever.’ And his disciples heard it. And when even was come, he went out of the city. And in the morning, as they passed by, they saw the fig tree dried up from the roots. And Peter calling to remembrance saith unto him, ‘Master, behold, the fig tree which thou cursed is withered away’“

(Mark 11: 12-21).

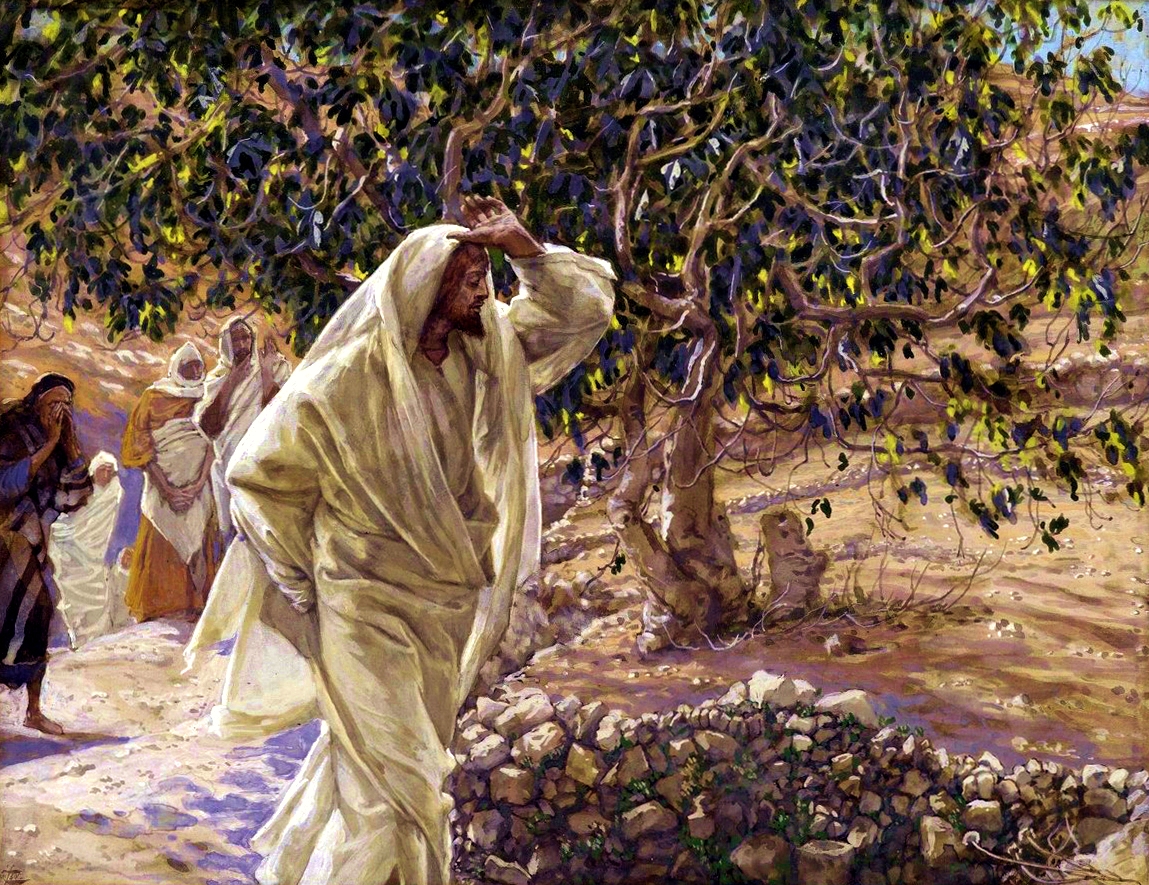

“The Accursed Fig Tree” by James Tissott

Many Christians have wondered at Christ’s seemingly harsh cursing of an innocent fig tree. Surely, many interpretations can be provided. In one of her sermons, author and preacher Joyce Meyer gives her own interpretation of this scriptural passage. She compares the unfruitful fig tree to Christians who are supposed to represent “the body of Christ.” (Parallels can also be made regarding individual and collective relationships among the Latter-day Saints.) Meyer makes the claim that like Jesus Christ, we are all weary and hungry travelers seeking food and shelter to alleviate our stress. From afar (similar to the unfruitful fig tree), local Christian congregations, along with the over all collective Christian Church body, can look like a soothing, safe place to be spiritually and emotionally fed. However, when we take a closer look (just as Christ took a closer look in the tree’s leaves for figs as He searched for fruit), we don’t find spiritual and/or emotional health and wellness, but rather a pseudo or false sense of community and shelter. Remember: From a distance, the fig tree had leaves (which meant it had figs too) and thus “fooled” Christ into thinking that delicious figs were hidden under the leaves to satisfy his hunger. Instead, the tree offered nothing, and so He cursed it to serve as an object lesson to His disciples. And, He also cursed the Pharisees and Sadducees for the same thing.

I also admire Dr. Scott Peck and use his wisdom for many of my posts. I’ll end this one with Dr. Peck’s words:

In pseudo-community a group attempts to purchase community cheaply by pretense.The essential dynamic of psuedo-community is conflict-avoidance. The absence of conflict in a group is not by itself diagnostic. Genuine communities may experience lovely and sometimes lengthy periods free from conflict. In pseudo-community it is as if every individual member is operating according to the same book of etiquette. The rules of this book are: Don’t do or say anything that might offend someone else; if someone does or says something that offends, annoys, or irritates you, act as if nothing has happened and pretend you are not bothered in the least; and if some form of disagreement should show signs of appearing, change the subject as quickly and smoothly as possible. It is easy to see how these rules make for a smoothly functioning group. But they also crush individuality, intimacy, and honesty“

The Different Drum: Community Making and Peace, p. 103.

Dr. Peck also discusses the temptation to flee from genuine interpersonal communal relationships or friendships because of the work involved in addressing differences. He says:

The struggle is over wholeness. It is over whether the group will choose to embrace no only the light of life but also life’s darkness. True community IS joyful, but it is also realistic. Sorrow and joy must be seen in their proper proportions (p. 102). In the task-avoidance, groups show a strong tendency to flee from troublesome issues and problems. Rather than confront these issues and problems, groups will act as if they assume it is their purpose to avoid them“

(p. 109).

Tired of trying to keep the peace at the expense of your own peace?

Here’s to resigning your post,

Julie