Making our suffering purposeful.

“In some way, suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning.” These words from Viktor Frankl changed my life! A Jewish psychiatrist from Vienna, Dr. Frankl endured the Nazi horrors at Auschwitz. When freed, he wrote the book, Man’s Search for Meaning in an effort to find meaning in the Holocaust. His conclusion: There was no meaning. There was no purpose. Yet, in efforts to retain his sanity, Frankl (and many of his fellow prisoners) found meaning in his own suffering. His profound insights helped me in reframing my own perceptions. Rather than recoil from inevitable suffering, I now work to face and embrace suffering as a means of spiritual growth. I don’t even call it “suffering” anymore. I’ve relabled suffering as an “opportunity to transcend myself.” I’m not talking about needless suffering or martyrdom which is masochistic, self-serving, and manipulative. I’m talking about the inordinate amount of time and energy we all spend in attempts to avoid pain and suffering—and we get nowhere. I finally decided to use my suffering as a means to getting somewhere. But before I could utilize my suffering, I had to legitimize my suffering.

Dr. Frankl clarifies this idea: “The ‘size’ of human suffering is absolutely relative. Suffering completely fills the human soul and conscious mind, no matter whether the suffering is great or little” (p. 64). Wow! Is Frankl actually validating my suffering as “real”—and not just a failure to “count my blessings?!” Talk about a relief. I can’t count the number of guilt trips I had traveled—wearing a heavy backpack that read: “Property of Julie Hawker who is a weak and ungrateful person.” I felt silly and stupid in my “insignificant” suffering. (Think about it: How many times do we tell each other at our Latter-day Saint Church meetings that our suffering doesn’t really matter compared to our Latter-day Saint pioneers and ancestors? I don’t want to dismiss their terrible suffering, but dismissing our own isn’t healthy either.) In our other social circles, I have heard others ask people to excuse them for complaining about their “first world” problems. Whether first or third world, historical or present, every human suffers. And in that suffering, they are hurting.

Here’s what my self-defeating suffering logic looked like in syllogistic form:

- Major Premise: Either my suffering is legitimate or irrelevant.

- Minor Premise: Victims of war, poverty, sickness, and criminal cruelty, legitimately suffer.

- Conclusion: Therefore, my “suffering” is irrelevant because I am not a victim of that type of circumstance. (Still, I feel pain and therefore, suffer.)

Years passed before I could see the fallacy in my circular reasoning; like a dog chasing its own tail. The only thing my faulty logic did was to perpetuate my guilt which served to increase my “suffering” all the more. Yes, gratitude helps to alleviate our pain, but my gratitude could not “unstick” me from my self-defeating dichotomous pattern of thinking. Besides, what right did I have to suffer in my ordinary circumstances brought on by my ordinary life? When I finally gave myself permission to suffer (and with Dr. Frankl as my role model), I learned to use my pain as a transcendental tool. He further elaborates:

When a man finds that it is his destiny to suffer, he will have to accept his suffering as a task; his single and unique task. He will have to acknowledge the fact that even in suffering he is unique and alone in the universe. No one can relieve him of his suffering or suffer in his place. His unique burden lies within the way in which he bears his burden. For us as prisoners…these thoughts were not speculations. They were the only thoughts that could be of help to us. They kept us from despair, even when there seemed no chance of coming out of it alive. Suffering had become a task on which we did not want to turn our backs. We had realized its hidden opportunities for achievement….the greatest courage, the courage to suffer”

(p. 99).

Dr. Frankl takes this notion a step further. He says we can choose our own attitude in any set of circumstances. Even in the terrible constraints of a Nazi death camp, humans have a choice of action:

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: The last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way. And every hour offered the opportunity to make a decision, a decision which determined whether you would or would not submit to those powers which threatened to rob you of your inner freedom. Naturally only a few people were capable of reaching great spiritual heights. But they were given the chance to attain human greatness through their apparent worldly failure and death, an accomplishment which in ordinary circumstances they would have never achieved. One could make a victory of those experiences turning life into an inner triumph, or one could ignore the challenge and simply vegetate, as did the majority of the prisoners”

(p.94).

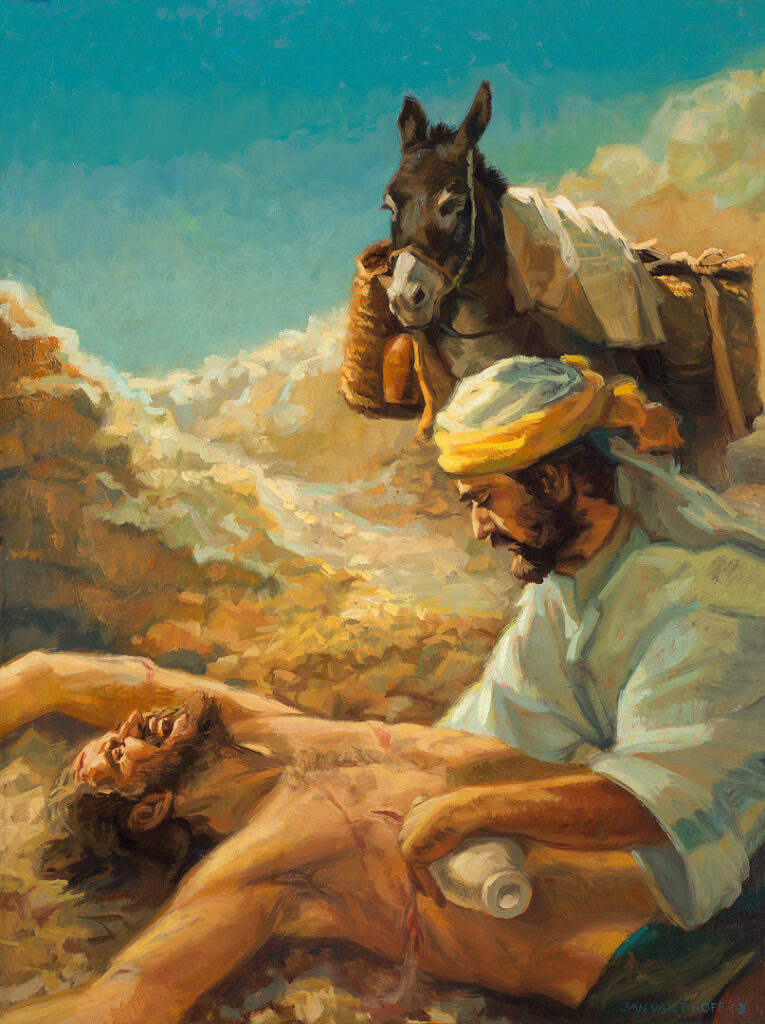

“The Good Samaritan”

Surely, most if not all of us, are familiar with the first line of the above quote. For me, the lines that followed were unfamiliar to me until I read Dr. Frankl’s entire book. The idea of embracing rather than enduring suffering to promote my spiritual and emotional growth completely changed me. With Jesus Christ as my tutor, I suffer to empower myself by accessing His power. In doing so, I ask myself the following questions:

- What can I do with this pain?

- How can I use this pain to help myself?

- What meaning is there for me in this pain or in this wound?

Authors Dorothy and Julie Firman in their book, Healing the Relationship, discuss the nature of wounds and suffering. When we view our suffering through a healthy perspective, our wounds become valuable. We learn about pain and suffering and recovery from our pain. When this becomes our strength, our wounds take on new meaning. The authors state:

As hard as it is to believe, every wound may be considered sacred. It guides us, as a beacon to our own growth, our own strength, our own uniqueness. Part of who we truly are is our own version of pain, our reaction to it, our interpretation of it and our healing from it. While it is convenient to think of a wound as the problem, the reason why ‘I can’t (do/be) this or that,’ an obstacle to growth, it may be enlightening and relieving to realize that it is a part of our growth. The sail on a sailboat is an obstacle to the wind. It blocks the free flow of the wind. Yet because of blocking the wind, it moves the sailboat. Without that obstacle the sailboat could not move. And so, too, for each woman who has a wound. It will help define, in an expanded way, who you are and can be”

(p. 126).

Truly, we can be proactive rather than feel and act victimized in our suffering. Rather than expending all my energy running away from pain, I face, brace, and embrace it: I batten down the hatches, hoist my sail, and face the wind!

Ahoy,

Julie