(Original Post Date: March 13, 2017. Updated in October 2024)

Faltering faith?

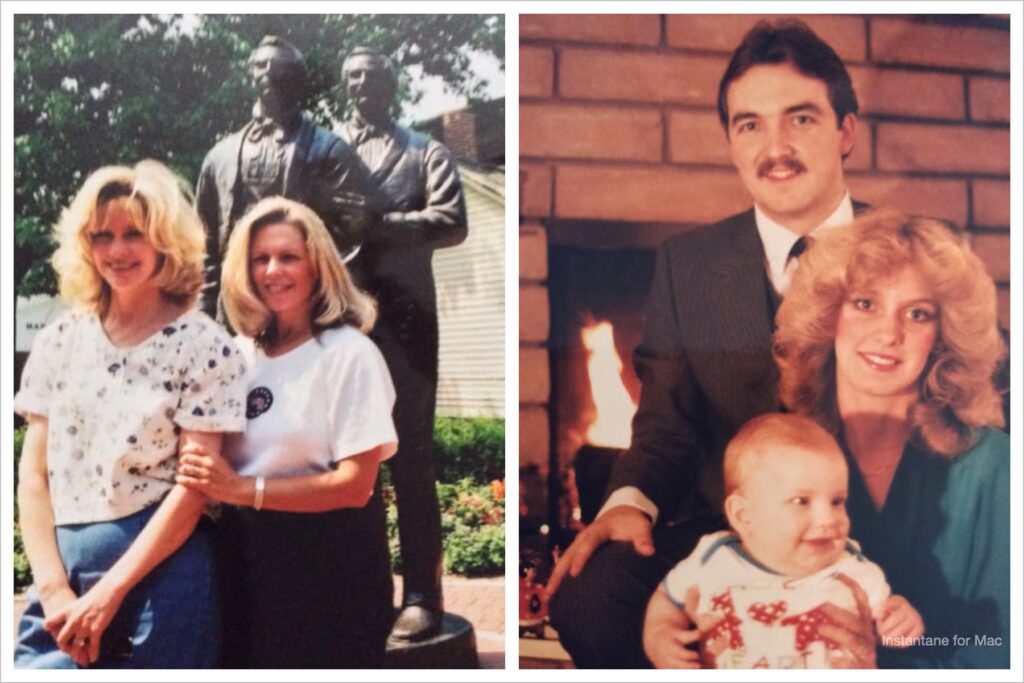

The 1980s were challenging years for me. I began 1980 as a newlywed and 1990 as a mom to four kids. One of my challenges involved questions of faith. Born and raised in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, I always had a rock-solid testimony of the gospel and of the Church. Still, like many American young women, I had questions regarding Church doctrine and Latter-day Saint culture. My older sister, Janet, was asking similar questions. Janet and I especially struggled with the issues I’ve listed below:

- The LDS doctrine of plural marriage and its practice during the 19the and early 20th centuries.

- Women and priesthood authority.

- Church administration and priesthood correlation resulting in women’s auxiliaries no longer having autonomy; instead they reported directly to priesthood authorities (This Church correlation program had been instituted 20 years prior).

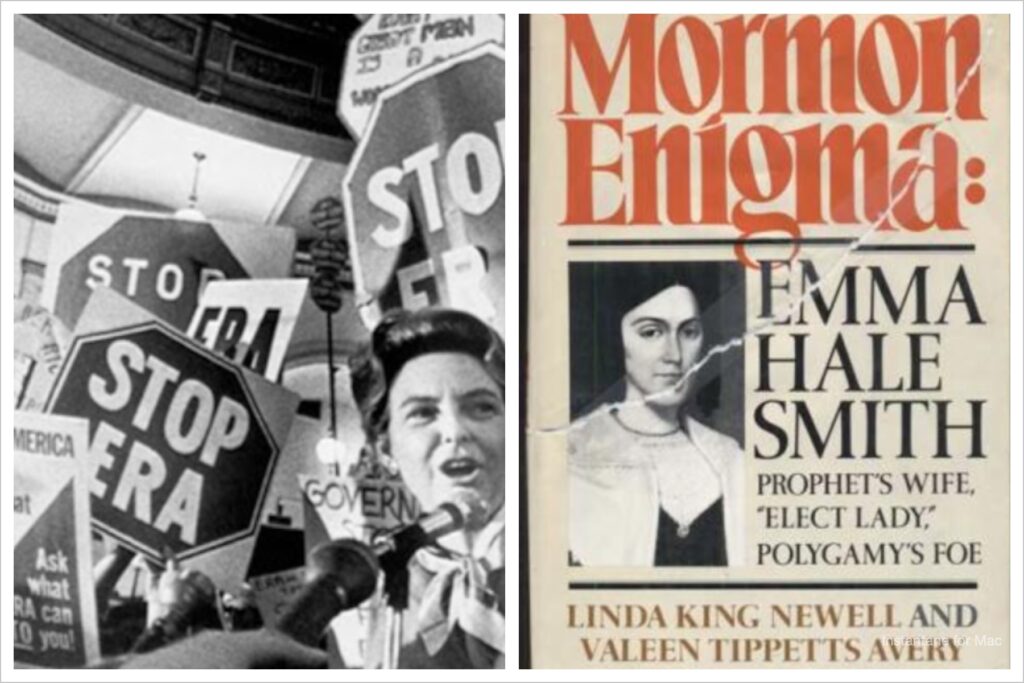

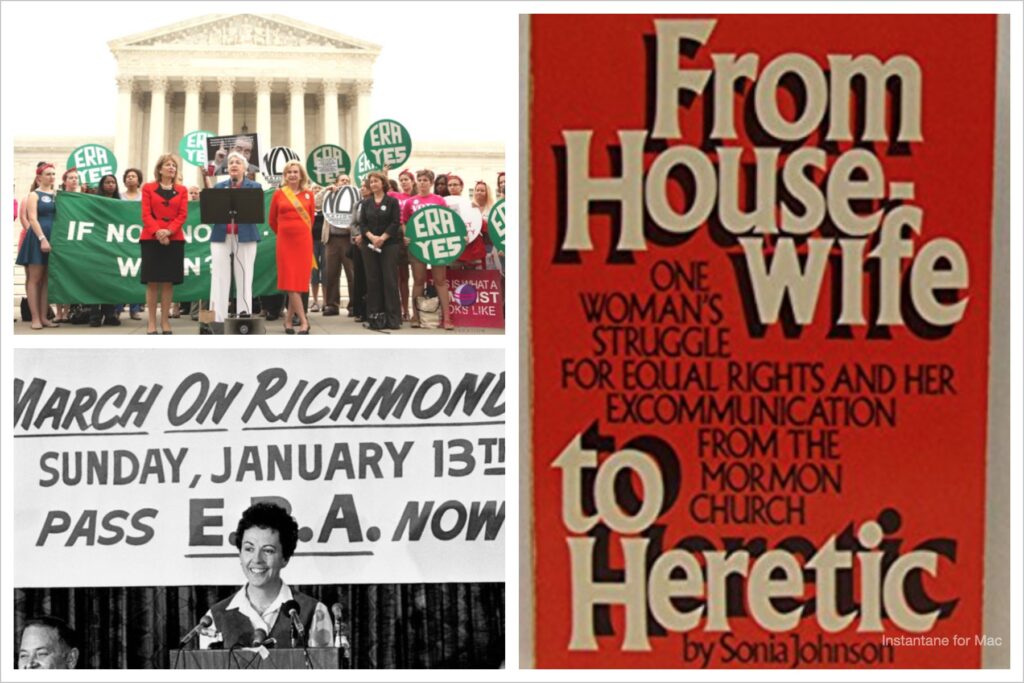

- The proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution (ERA) for gender equality. (Ultimately, the proposed amendment failed to pass, but its bitter political divisiveness spilled into the Church membership.)

- Sonja Johnson, founder of “Mormons for ERA,” had recently published her book, From Housewife to Heretic, making her one of ERA’s national standard bearers. Having been excommunicated from the Church for apostasy, Johnson made national news and appeared on the national talk show circuit to speak against the Church’s patriarchy and its stance against the ERA. Johnson also spoke at the 1980 National Democratic Convention.

- The recently published book, Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith, Prophet’s Wife, Elect Lady, Polygamy’s Foe, written by LDS historians Linda K. Newell and Valeen Avery, gave some credibility to Church critics. Their book is a troubling and unflattering account of Joseph Smith’s character, his revelation and practice of plural marriage, and his troubled marriage with Emma. Access to Church archives was much more limited, but the same could be said about access to secular information. The internet would not be invented for nearly 20 years; until then, research was difficult and results were often scanty and opaque. Janet and I knew several friends who had read the book, and it rattled their faith. Rightly or wrongly, Janet and I decided not to read the book due to its contentious nature. Besides, we didn’t want to further undermine our faith. (Years later, I read the book; it wasn’t a big deal to me. If anything, I felt reassured knowing that early Church leaders and members had human frailties and struggled with gospel principles–just like the rest of us.)

- Church leaders strongly discouraged mothers from working outside the home. I was a stay-at-home mom for many years, and I have no regrets. I surely understand the wisdom in this counsel. Still, I felt guilty for wanting a teaching career while furthering my education to qualify. I began teaching college in my late 30s—still, some of my LDS women friends negatively judged me.

Above photo: Janet and I in front of the “Joseph and Hyrum Smith” memorial statue at Carthage Jail, Illinois in 2001. Rick and I with our firstborn son in 1981.

Janet and I had grown up on the swells of second-wave feminism. At that time, many young LDS women in our generation did not aspire or desire a college education. During the 1970s, President Spencer W. Kimball helped to change this mindset by encouraging women to pursue higher education. Additionally, he instituted the policy allowing women to offer the opening and closing prayers in Sacrament meeting, and later established the first annual General Women’s Conference gathering in October 1978. (I was a BYU student at the time and was able to attend.)

Still, the idea of an LDS “full-time working mother” with career aspirations was strongly discouraged. Throughout the 1980s, the Church magazine, Ensign, featured articles about highly educated women who chose to forego careers and use their educational skills for full-time mothering. Please don’t misunderstand: I support and value the role of stay-at-home mothering; I was a stay-at-home mom for many years. My point is to emphasize the mixed messages and mixed emotions women experienced as societal and social change offered new choices and increased opportunities.

Also at that time, LDS women who got married (including Janet and I) tended to be very young and expected to bear children soon after marriage—lots of children. To our eternal gratitude, our dad was a college instructor so instilled within us the value of higher education. My mother was pregnant with her fifth child when earning her bachelor’s degree while Janet and I were teenagers. So, my sister and I worked hard to obtain our college degrees (and later master’s degrees) after becoming wives and mothers.

The image below is the March 1983 Ensign magazine cover. This was the first issue dedicated exclusively to Latter-day Saint women. Admittedly, Janet and I were a bit disappointed with the cover featuring a bread-baking mother wearing a frilly apron.

As young mothers, my sister and I were pretty much anomalies among our peers in terms of our aspirations. For years, we struggled under the pressure to fit into the traditional “Ultimate Mormon Woman” mold. Twentieth century Latter-day Saint cultural norms (up through the 1980s) basically looked like this:

- Women were expected to have lots of children, stay at home, and cultivate joy in homemaking. (And, I’ll be the first to say, children seemed to have thrived more in this environment than they do today.) Women who worked outside the home were often judged by others in their “failure to follow the Prophet.” (After having one child, I worked part-time for a year. Two of my friends and my bishop admonished me “to follow Church counsel.” Years later and as a mother to four children, I studied longs hours while pursuing my master’s degree. More than a few of my LDS friends criticized me for “neglecting” my children while pursuing my “selfish desires.” Obviously, not all LDS women cast such harsh judgment. But even today, women (inside and outside the Church) can put tremendous pressure on each other.

- Postponing children and having “small families” was discouraged.

- Artificial birth control was also discouraged. Many discussions in Church and among LDS women centered around this very thorny issue. The opinions of prophets and apostles, who had lived during the turn of the 20th century, were often quoted in Church lessons and in personal conversations. Also, the prophet Joseph Fielding Smith and David O. McKay were specific in their counsel. President McKay said, “Where husband and wife enjoy health and vigor . . . it is contrary to the teachings of the Church to artificially curtail or prevent the birth of children. We believe that those who practice birth control will reap disappointment by and by” (Ensign, May 1971). Time and again, I struggled and prayed because of this!

- Gender roles were much more pronounced. Below is a link to an Ensign article published six years before I was married. The article counsels husbands and wives. Here’s a few specifics from the list for husbands: “Be man enough to change the baby’s diapers . . . and occasionally bathe the children.” And some specifics on the list for wives: “Prepare good meals for him, especially when he is late for dinner. Take telephone messages for him carefully and see that he gets them. Free the telephone when he needs it.” The rest of the article can be accessed at: https://www.lds.org/ensign/1973/06/for-husbands-and-helpmeets?lang=eng Again, I’m not suggesting that this advice is inherently wrong. My point is to illustrate mainstream LDS expectations during that time period.

Like I said, my sister and I grappled under these pressures in striving to “become.” But still…neither of us wanted to give birth to congregations of children. (I eventually had four children and Janet had three.) We both wanted careers; Janet worked as a middle-school teacher, and I eventually became a college instructor. Unlike me, Janet enjoyed (and is very proficient) at baking. We both made sure our homes were clean and orderly, and we were both good cooks. (I didn’t enjoy cooking but knew the importance of nutritious meals and family dinnertime.) Neither Janet nor I enjoyed sewing (Janet enjoys needlework) even though we had sewn a lot of our own clothes in high school. During my early years of marriage, I did some sewing until it was no longer cost-effective. Still, I felt little to no joy in sewing. Or baking. Or crafting. Or canning. Or quilting.

1987: My daughter, Erica’s Blessing Day

As Janet and I got older, we grew more confident in our own judgment and decision-making. And, we learned to rely more on the Spirit for guidance and affirmation and less on judgment or advice from others. In short, we learned to separate Church culture from Church doctrine. Most importantly, we learned to care more about the Lord’s opinion of us than others’ opinions. We have lived our lives as devoted, active Church members despite our frustrations, doubts, and fears. (One fear, however, plagued us the most: the doctrine of plural marriage. No matter how much Janet and I talked and tried to console each other, we couldn’t reconcile what we called “the crazy aunt in the basement” doctrine. I will revisit this topic later in this post.)

Do you, dear readers, have similar feelings? Do you struggle with your faith? Do you struggle to “fit in?” Do you feel insecure or fearful regarding various aspects of LDS culture, Church policy, doctrine, or leaders? Are you rattled by competing voices within and without the Church? Are you troubled by Church history? Do you feel guilty for questioning your faith? Be assured, you are not alone.

In the rest of this post, I discuss how changing societal norms and philosophies can help inspire but also undermine our faith in the gospel, the Church, its leadership, doctrines, and how we can navigate tempestuous social and political divisions while sustaining our personal faith. Here’s the good news: our faith in Jesus Christ can supersede all of our doubts. He is a soft place to fall when we take our doubts and fears to Him.

“Touch of Faith” by Yonugsung Kim

As members of the Church, we still face enormous challenges living in the modern world. As we know, many people are leaving the Church because they have lost faith in Church leaders, doctrine, “The Proclamation of the Family,” and other moral and ideological differences regarding Church policies and belief systems. In the rest of this post, I discuss and briefly define some of the present-day ideological movements influencing Western societies and their public policymaking—particularly in North America, the United Kingdom, Western Europe, and Australia. My purpose is not to condemn political, social, or cultural ideologies. Rather, I emphasize the potential hindrances and harms to personal and community faith when any ideology is excessively interpreted and even dogmatized. In the past and in the present, advocates and activists have often used extreme and divisive methods in getting the public to comply to their belief systems and/or ideological edicts. Throughout this post, I offer some suggestions that might help in sustaining our personal faith as we navigate today’s ideological waters.

Influences That Can Undermine Personal Faith

So, how do we get from doubt to faith to peace? How do we attain and sustain our faith and peace? Faith in Jesus Christ. This has been the only answer that has brought me peace. I have learned that having faith is not about having a perfect knowledge or understanding of anything. I do know that Christ knows and understands everything. By having faith in Him, I have been able to weather the contentions—and often the deceptions—that ideological storms ferment. Attaining, sustaining, and increasing our faith is often a rocky road. Spiritual and emotional transcendence are difficult task masters. Below, I humbly offer some of my own observations and life experiences when wrestling with my own faith crises:

- Reasoning. We can reason ourselves out of our faith.

The saying, “Pride goeth before the fall,” is so true. Unless I stay humble in my relationship with God, along with fostering my over all humility, I can reason myself right out of my faith. This can happen while waiting for my prayers to be answered, or if my prayers are not answered in the way I had hoped. My faith also shakes when I feel frustrated by personal weakness, or when feeling vulnerable to expectations within the Church. If I’m not careful, my pride and resentment injures and undermines my faith.

In studying the Book of Mormon, I’ve decided that Laman and Lemuel (from an intellectual standpoint) were often the reasonable ones in Lehi’s family. They had ample reasons to murmur and complain about their circumstances. After all, they had left behind their home, friends, wealth, and position in Jerusalem to wander for eight years in the desert. Furthermore, their resentment and frustration was rooted in the original reason for the family’s departure: the father, Lehi, claimed to have “dreamed a dream one afternoon while laying on [his] bed.” Even with possessing great faith, this kind of upheaval would be upsetting to anybody. We know that from time to time, Laman and Lemuel were forcibly humbled. But, their humility and faith quickly evaporated when faced with obstacles; their reasoning always obliterated their faith. Conversely, Nephi suffered the same hardships and uncertainties yet still had the ability to bear these challenges with grace and patience. Why? Because Nephi exercised consistent faith and humility enabling him to receive his own sustaining spiritual witness—particularly from the very start of their journey. Rewarding Nephi’s faith, the Lord granted him the same vision Lehi had seen. We read how the Spirit continually sustained Nephi’s faith and softened his heart as he endured great suffering and seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Nephi’s words reflect humility and faith:

We must lay aside our sins, and not hang down our heads, for we are not cast off. Nevertheless, we have been driven out of the land of our inheritance, but we have been led to a better land, for the Lord . . . Wherefore, my beloved brethren, reconcile yourselves to the will of God, and not to the will of the devil and the flesh; and remember, after ye are reconciled unto God, that it is only in and through his grace that ye are saved”

(2nd Nephi 10: 20-22).

“Father Lehi’s Dream”

Like Nephi, we can attain a better land—not just a temporal land but a spiritually, emotionally, and intellectually better land while trudging through our fears, doubts, and anxieties along the way.

I’m also inspired by feisty Jacob who “wrestled with an angel” when trying to obtain the Lord’s blessing. Genesis, Chapter 32 details Jacob’s experience the night before he was to meet his estranged brother, Esau. Although the Old Testament is not clear about what exactly transpired, we do know that Jacob wrestled all night with the angel. Jacob tells the angel, “I will not let thee go, except thou bless me” (verse 26). After breaking his thigh bone during the struggle, Jacob received the Lord’s blessing. I like the scriptural use of the word “wrestle.” I think God likes a good wrestle. I know from experience that when I wrestle hard enough, the Lord comes through.

“Jacob Wrestling With an Angel,” by Lelore

Surely, we navigate our own journey of faith. Each one of us sees and interprets the world through our own lens. While navigating life, we can remind ourselves of our skewed vision and perception. Ignorance, ambiguity, weakness, and prejudice taint our lens and thus distort our judgment. The principle of faith is, by its very nature, ambiguous. This makes me crazy at times; I like certainty, I like specifics. I think most of us do. The process of seeding, growing, sustaining, and increasing faith starts out simple enough, but as our faith is tested and tried, continually growing and sustaining it can be exceedingly difficult. Karl Marx claimed that religion is “the opiate of the masses.” On the contrary, religious faith requires enormous amounts of self-discipline, humility, determination, and self-examination. A faith journey is not for the faint of heart.

2. Contemporary academic philosophies, societal and global policies, and various forms of advocacy. These competing ideologies and their methods to gain compliance can contribute to divisiveness within ourselves, our families, friends, and fellow church members.

I said earlier I had graduated from high school and entered college in the late 1970s. Later, I taught general education courses at a California state university for nearly 25 years. As both student and college instructor, I witnessed the decades long process of the scholarly seeding, incubating, germinating, and eventual harvesting of influential present-day philosophies and social theories such as “post” postmodernism, post-structuralism, feminism, critical theories, etc., and their influence on Western societies. Although critical race theory originated in legal studies, the social sciences and humanities helped grow and blossom this theory along with other critical and intersectional theories. Postmodernism seems to have birthed them all. I’m no expert, but during my academic career, I was obligated to “swim” in these philosophical theoretical waters and implement them in my classroom.

I write this particular section because the cultural and societal implementations of critical theories have greatly influenced Western societies in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Western Europe. In the late 1980s critical theories gained traction in academia and by 2001, they had culminated and solidified from a set of abstract “theories” into a major influential force Western universities. These abstracts had become legitimate analytical tools for interpreting Western Civilization and its tenets, institutions, and ideals—while searching for “oppressive patriarchal, racist, and inequitable structures” in Western societies. Eventually, this method of interpretive analysis became a structural framework within many university disciplines. Research, pedagogy, classroom environment, campus culture, interpersonal communication—everything was now scrutinized under critical theories’ interpretive lens in efforts to “see” how “problematic” social and economic power structures become “visible.”

Here’s a few definitions below. If you find them boring, dear readers, feel free to skip this section. It’s rather long and tedious. (Honestly, writing this section was very hard and very tedious for me!)

A Critical theory is chiefly concerned with revealing hidden biases and under-examined assumptions, usually by pointing out what have been termed ‘problematics,’ which are ways in which society and the systems that it operates upon are going wrong. . . . The scholar-activists [examine Western societies] . . . power, language, knowledge, and the relationships between them. They interpret the world through a lens that detects power dynamics in every interaction, utterance, and cultural artifact—even when they aren’t obvious or real. This is a worldview that centers social and cultural grievances . . . revolving around identity markers like race, sex, gender, sexuality, and many others . . . it adopts its own interpretive frame through which it sees the entire world view of power and its ability to create inequality and oppression” (“Critical Cynical Theories,” 2020. Pluckrose & Lindsay, Introduction).

Critical theories. We can see its impact on the world . . . and the activists’ assertions that society is simplistically divided into dominant and marginalized identities and under pinned by invisible systems of white supremacy, patriarchy, heteronormativity, cisnormativity, ableism, etc. . . We find ourselves faced with the continuing [deconstruction and] dismantlement of categories like knowledge and belief, reason and emotion, and men and women, and with increasing pressures to censor our language . . .” (Introduction).

Postcolonial theory looks to deconstruct the West, as it sees it . . . to achieve a specific purse, ‘decolonization,’ the systematic undoing of colonialism in all its manifestations and impacts. The key idea in postcolonial theory is that the West constructs itself in opposition to the East, through the way it talks. [Such as] ‘We are normal, and they are exotic.’ ‘We are advanced, and they are primitive.’ The East is constructed as the foil to which the West can compare itself. The term ‘the other’ or ‘othering’ is used to describe this denigration of other people in order to feel superior. Postcolonialism views knowledge and ethics as cultural constructs maintained by language; people who believe in [this] theory can be really hard to have discussions with. They see evidenced and reasoned arguments as Western constructs, and therefore invalid or even oppressive. People who disagree with them are seen as defending racist, colonialist, or imperialist attitudes. This mindset hears ‘othering’ and ‘appropriation’ in everything.

The analytical process of deconstruction of Western ideals and global influences includes the analysis of attitudes, beliefs, speech, and mindsets, which are sacralized or problematized. These they construct simplistically from assumptions that posit white Westerners (and knowledge that is understood as ‘white’ and ‘Western’) as superior to Eastern, black, and brown people (and ‘knowledges’ associated with non-Western cultures) despite that being the stereotype they claim to want to fight” (p. 64, 74).

Many of us have heard about critical race theory or the CRT movement. In his book, Critical Race Theory, Richard Delgado defines it as:

The critical race theory (CRT) movement is a collection of activists and scholars engaged in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power. The movement considers many of the same issues that conventional civil rights and ethnic studies discourses take up but places them in a broader perspective that includes economics, history, setting, group and self-interest, and emotions and the unconscious. Unlike traditional civil rights discourse, which stresses incrementalism and step-by-step progress, critical race theory questions the very foundations of the liberal order, including equality theory, legal reasoning, Enlightenment rationalism, and neutral principles of constitutional law” (Third Edition. NYU Press, Kindle Edition, p. 3).

Like all critical theories, queer theory is nuanced and complicated. Judith Butler was one of its pioneers in expanding gender identity outside the binary (man and woman) heterosexual norm.

Queer theory functions to complicate existing academic frameworks, and conceptions of social relations, by deconstructing the dominant, heteronormative structures undergirding extant scholarship (Marinucci, 2010). One theoretical strategy relies on an insistence on the social construction of gender and sexuality (see Butler, 1990). Theories of social construction claim that human identities are not inherent or essential (that is, having an essence), but rather emerge out of social relations and discourse. In Butler’s (1990) work, she understands gender as produced through repetitive practices of personal and social practices. In other words, one’s gender does not exist a priori discourse, but instead is constructed by characteristics and experiences. At the base of social constructionist theories is the assumption that, since identities are constructed, they can always be constructed otherwise” (Barnett, Joshua Trey, and Corey W. Johnson. “Queer.” Encyclopedia of Diversity and Social Justice, Sherwood Thomson (ed.). Rowman & Littlefield, 2015, pp. 581–582).

“Woke” or “Wokeism” is a 20th century word that became more prominent during the last 15 years in academia. Now, the term has become mainstream with varying definitions. According to Laura A. Roy, ” . . . “White accomplices [meaning white people] should strive to be woke enough not to call themselves woke and instead strive to embody this state of being by building with people of color. … Be in a perpetual state of learning and be woke enough to know you are never woke enough” ( Teaching While White: Addressing the Intersections of Race and Immigration in the Classroom. Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, 2018.)

Dr. James Lindsay offers this definition:

In brief, ‘woke’ means having awakened to having a particular type of ‘critical consciousness,’ as these are understood within Critical Social Justice. To first approximation, being woke means viewing society through various critical lenses, as defined by various critical theories bent in service of an ideology most people currently call ‘Social Justice.’ That is, being woke means having taken on the worldview of Critical Social Justice, which sees the world only in terms of unjust power dynamics and the need to dismantle problematic systems. That is, it means having adopted [Critical]Theory and the worldview it conceptualizes.

Under ‘wokeness,’ this awakened consciousness is set particularly with regard to issues of identity, like race, sex, sexuality, and others. The terminology derives from the idea of having been awakened (or, ‘woke up’) to an awareness of the allegedly systemic nature of racism, sexism, and other oppressive power dynamics and the true nature of privilege, domination, and marginalization in society and understanding the role in dominant discourses in producing and maintaining these structural forces. Furthermore, being woke carries the imperative to become a social activist with regard to these issues and problems, again, on the terms set by Critical Social Justice. This—especially for white people—is to include a lifelong commitment to an ongoing process of self-reflection, self-criticism, and (progressive) social activism in the name of Theory and Social Justice [also known as] antiracism” (https://newdiscourses.com/tftw-woke-wokeness/).

To advance these ideals within universities (and later in corporate and government entities) bureaucracies were created to set, expand, and sustain the principles of equity, diversity, and inclusivity by introducing initiatives, strategies, practices, and policies. Also, by including similar strategies in learning objectives and course work, faculty and students could serve as “active participants” in social advocacy. Not surprisingly, professor objectivity in the classroom was less essential.

Around 2010, critical theory went mainstream in America and other Western countries. Any government and cultural acceptance of critical theoretical interpretive methods and “other ways of knowing” would help to redistribute, reshape, and even dismantle the Western world’s social and economic power structures to a more inclusive and equitable global community. Focusing on societal disparities would help to “deconstruct” or tear down Western institutions, their “inherent bias,” and public policymaking while advocates built a sort of new world order.

Back then (and from my own perspective), all of this sounded great “on paper,” and there’s no question that positive societal changes have been made—but not without unintended (or perhaps intended) consequences, harms, and backlash after 25 years. Part of the problem was/is the promotion and acceptance of ideological positions and theories—accompanied by their influential moral compasses—were introduced and implemented without enough or any empirical evidence or realistic contexts regarding potential societal impacts. Rightly or wrongly, societal perceptions and interactions between individuals and groups have since changed; advocates have assigned—and much of society has accepted—the importance of collectivism over individualism. People are carefully scrutinized, categorized, and then morally judged based on their characteristics (some of which are immutable such as skin color) and classify each individual as an “oppressor” or as “oppressed” within society. Such “isms” include sexism, heterosexism, racism, ableism, classism, ageism, tokenism, colorism, etc. Society now seems to place greater emphasis on what group you belong to rather than who you are as an individual.

Opponents of critical theories and critical social justice believe that too much of critical social justice advocacy and activists have become quasi-religious in their views and in their methods in getting the public to comply. For instance, our society has become all too familiar with “cancel culture” and its instigation of public guilt, shame, fear, and harsh punishments for those who question or disagree with its social justice edicts. Too many individuals—along with their careers and families—have been destroyed due to angry zealotry. I believe that regardless of noble or kind intentions, the ends don’t justify the means.

Despite the good and needed societal and cultural changes resulting from critical theories and their social justice beliefs systems, other thorny issues have emerged. For example, advocates are divided over the blurry boundaries between encouraging public compliance and enforcing it. And, at what point does a liberal approach to education and public policy become an illiberal approach when it begins to pit free speech and expression against “hate speech,” subjective truths and “lived experience” against objective truth, or opposes the scientific method? When do the rights of the group supersede the rights of the individual?

To increase analytical discernment regarding belief systems, their methods, advocacy, and activism, we can examine their use of language, definitions, contextual meanings, and strategies to gain the public’s compliance in the following ways:

A. Do advocates want power? Control?

What methods do their advocates use? Do they use fear, shame, or guilt to get people to comply?

Do they rely on suppression or censorship?

What are their moral codes and edicts?

How do they enforce their moral code? What are their punishments for those who don’t comply?

B. Look for historical patterns and examples of “noble” or utopian ideas that resulted in authoritarianism, tyranny, and totalitarianism.

Any belief system, philosophy, and ideology—no matter how righteous and noble its intentions becomes harmful and destructive when taken to extremes.

History repeats itself, and we need only look to 20th century atrocities to find examples of failed utopias in the form of authoritarian rulers and totalitarian governments. Their attempts to create and sustain egalitarian societies have thus far resulted in mass starvation, ethnic cleansing, political imprisonment and torture, religious persecution, forced collectivization, forced labor camps, and other ravages. Despite their imperfections, I believe the ideals of Western Civilization have been more successful in ultimately producing, evolving, and expanding liberties and freedoms than any other ruling authority or government in world history. Until Jesus Christ comes again and sorts out our global messes, I believe Western ideals are worth preserving and defending. Surely, Western societies can continue to evolve using democratic principles and consensus for a free society.

“Title of Liberty” by Minerva Teichert

C. Search for dogmatism or a tendency to push principles as incontrovertibly true without considering any evidence or the opinions of others.

One of America’s founding principles differentiates between a democratic government “by the people and for the people,” versus a theocratic government that installs leaders who are members of a religious clergy where the state’s legal system is based on religious law. While teaching critical thinking, I taught my students (many of whom never participated in organized religion) to analyze, discern, and recognize ideologies, belief systems, and their moral imperatives—which claim to be emancipating, unfettered, and liberating—but are still closely structured like an organized religion or a closed society. I told my students that my life-long membership in and devotion to an organized religion, helped me to better analyze and understand the past, present, and potentially future moral imperatives and principles within American culture, public institutions, government entities, and public policymaking. I also told them that campus communication climates in universities and colleges felt increasingly dogmatic coupled with a moral “religious” fervor or zeal. Again, because so many of my students had never stepped inside of a church, they were clueless as to what religious zeal or devotion “felt” like.

D. Look at their methods in getting people to comply.

Do their methods use fear? Do you feel intimated if you don’t comply? Do the leaders and followers use group pressure in attempts to make you feel guilty or ashamed if you don’t conform or if you make a mistake? Do you feel anxious when trying to follow their rules or moral codes? Do you feel pressure to “voluntarily” comply, conform, or obey their rules? Are you afraid of what they will say or do if you question or don’t follow their rules or moral code? Are you afraid to associate with dissenters or people who question the rules or the moral code? Do you stay silent to avoid being lectured, criticized, singled out, or punished? Do you “go along to get along?” Are you afraid to state your personal opinions?

Do their methods include secrecy and subterfuge? For example, do they use anonymous “tattle-tale” committees to report incorrect language and behavior to higher authorities?

E. Look at the punishments given to those who question or fail to comply.

In one of his letters to the Corinthians, the Apostle Paul writes, “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall i know even as also I am known” (1 Corinthians, 13:12). I have watched impressionable students peer through the lenses of critical and intersectionality theories. And that’s a good thing. However, when students are not exposed to differing philosophies and contexts, their ability to think critically, to reason, and to effectively communicate is hampered and distorted. Instead, a heavy reliance on feelings, emotion, combative language, together with a pressure to conform, can encourage zealotry in students while ushering in new forms of bigotry, hatred, and/or oppression. I see it now as I watch Western societies around the globe descend into division, chaos, hatred, and anarchy—because too many peer through a dark lens.

I believe we can increase or decrease our personal faith in accordance to the lens we choose to “see through a glass, darkly.”

If we seek to stabilize or increase personal faith as it pertains to Latter-day Saint doctrine, history, leadership, or fellow Saints, we might consider a careful inventory of our own sins and weaknesses. It’s so easy to focus on the sins and weaknesses of others—especially those with whom we disagree—while diminishing or own weakness. Even though I constantly fail in trying to fully live gospel principles, I do know that pure love, compassion, and kindness are not selective or conditional.

In October, 2022, Elder Ahmad Corbitt, who serves in the Young Men’s General Presidency in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints addressed activism against the Church during his talk to Church endorsed chaplains:

Brother Ahmad S Corbitt: How activism against the Church can blind, mislead ‘valiant’ souls

www.youtube.comBrother Ahmad S. Corbitt, first counselor in the Young Men general presidency, spoke to Church-endorsed chaplains in the Conference Center Theater on Oct. 4,…

4. Intellectual ability can increase arrogance and pride

I believe arrogance and pride can be the twin blights within academia and in today’s society. These blights can easily affect graduates of higher education. I have listened to brilliant scholars and graduate students who, because they have acquired a significant amount of secular knowledge (often insular knowledge) believe their judgment and knowledge beyond question; they personify a type of moral superiority.

Canadian professor, Dr. Jordan B. Peterson, frequently writes and produces podcasts about “the arrogance of the intellect.” See https://youtu.be/nNpU1LOFDok?feature=shared Dr. Peterson claims that knowledge and wisdom are not the same. I agree; I’ve listened to professors who are knowledgeable yet seem to be lacking in some wisdom—or even a bit of common sense. Please don’t misunderstand me. I don’t fault higher education or educated people. Surely, human nature makes all of us vulnerable to variations of pride and arrogance. These twin human frailties distort reality along with our perceptions of self, others, and truths.

A couple of years ago, a young, very intelligent, and highly educated friend of mine stated incredulously, “I can’t believe that you, Julie, would put your trust in the Prophet and Apostles before your own judgment.” I responded, “That’s not what I believe. I put my full faith in Jesus Christ. When I humbly follow Christ, He leads me to righteous conclusions; this process helps to increase my faith in the Latter-day Saint Restoration and its gospel teachings.” Over the years, I have observed my friend’s diminishing faith. Last I heard, he has left the Latter-day Saint community. There can be a fine line between our expertise or intellectual prowess and our humble faith.

5. Cultural influences can undermine our faith

I said earlier that present-day cultural trends in Western societies tend to cast aside and even ridicule faith in God or in organized religion—particularly Christianity. Humanists and secularists encourage us to develop a complete faith in ourselves and in our own abilities. This includes an individual’s self-actualization, gender self-identity, sexual identity, group or ethnic identity, and so on. Again, I’m not claiming that developing and celebrating ourselves is wrong. Rather, I’m talking about the emotional and spiritual harms caused by an excessive focus on self. Humans have an innate need to believe in and live for something “higher” than themselves. (We this need exemplified in the passion of social justice activists, climate change, activists, and in the zeal in religious believers.) Obviously, lacking a desire to transcend ourselves, our self focus often creates unhealthy levels of anxiety, depression, attention-seeking mindset and behaviors, and narcissism—all sources of unhappiness and discontent. The Western societal emphasis on self-actualization seems to exemplify Nephi’s ancient prophesy in the Book of Mormon:

Their land is full of idols; they worship the work of their own hands, that which their own fingers have made. And the mean man boweth not down, and the great man humbleth himself not”

(2 Nephi 12: 8-9).

Truly, our focus on Jesus Christ helps to alleviate self-centered and self-destructive mindsets and behaviors.

“Divine Companion” by Youngsung Kim

Feeding Personal Humility Increases Faith

I cannot emphasize this principle enough. Alma taught that faith comes from submission to the word of God. In the Book of Mormon Alma observed the Zoramites and how “they were cast out of the synagogues because of the courseness of their apparel…” (Alma: 32). Alma was hopeful that the Zoramites’ subsequent humility had caused a change of heart in allowing the seeds of faith to grow within them. Elaine Shaw Sorenson in her article, “The Seeds of Faith,” gives us significant insight:

Alma’s lesson has meaning today. Latter-day Saints seem naturally inclined to focus upon their works. This propensity to rely so heavily on works that document obedience seems to be an outgrowth of our present technological, behavioristic society, which places so much emphasis on observable achievement. Increasingly encumbering and complex, family, career, and even Church activities can disperse attentions toward multiple distractions among tasks and programs. Illusionary time and goal management techniques, if not grounded in a basic Christian nature, can further contribute to task-based rituals and repetitions in life. By extending ourselves laterally outward in noisy worldly ways, we risk becoming swallowed up in the proud illusion of progress (Alma 31: 27), when what we need is to extend quietly inward toward humility and upward toward God. As with the apostate Zoramites who lacked the essential humility that leads to faith, the achievements and prosperity that embellish our lives become meaningless trappings of mortality with no eternal significance without faith. Doing home teaching, earning a scout merit badge, or doing other assigned acts of service can become little more than offerings on the Rameumpton (Alma 31: 21) if our hearts are not earnest and our daily nature not Christian“

(BYU Religious Studies Center).

“The Sower”

Genuine humility rather than compelled humility acts as a forcefield against fiery darts of contention, agitation, and self-doubt. These brands of arrogance and pride are the antithesis of humility because they claim little to no need of Christ (or in any kind of higher power). Like some secularists, religious agitators might also claim having superior knowledge thus knowing what’s best for all of us. In any case, I prefer to invest my faith in Jesus Christ and also in the Prophet rather than in fellow Church members.

At the beginning of this post, I talked about my concerns regarding the LDS doctrine of plural marriage. This doctrine fueled my feelings of resentment, dread, and indignation. For years, I pushed away these feelings and refused to think about polygamy. As my personal relationship with God increased, I decided to “confront” God about (in my view) this “reprehensible” doctrine. His response to me was swift and sure. I received a very clear and strong impression: my questions and concerns would not be answered until I sincerely humbled myself. This meant clearing my mind and heart (at least temporarily) of resentment and prideful negativity pertaining to this doctrine. I will admit; it took some mental exertion and sustained effort on my part to get there. That weekend, I planned to watch the LDS general conference knowing that the Spirit would soften my heart and open my mind. After Sunday’s concluding session, I drove to the church parking lot, sat in my car, and prayed for some answers. I did not receive detailed information, but a loving God provided me with some insights regarding plural marriage. If anything, I came away with more questions than answers. Nevertheless, I felt heard, validated, and reassured by my Heavenly Father. Even more, I felt respected. I felt His love. I felt peace and joy. And that’s all that mattered to me. I drove home with a satisfied and thankful heart.

Whenever doubts or questions inflict my soul, I work to humble my heart and take my concerns to God. His counsel, His grace, and His love are infinitely more cathartic and therapeutic than anything or anyone else on earth. Our inner peace that comes from God and our Savior is able to transcend any doubt, anxiety, fear, or even anger we may have in regard to our Church leaders, fellow members, doctrine, and/or local Church culture.

Becoming comfortable with uncertainty

Faith is the antithesis of certainty. I had to learn to feel comfortable with unanswered questions. I have learned to suspend judgment of anyone or anything before genuinely seeking answers and insight through the Spirit. Additionally, the best way (for me) to overcome doubt is to water the righteous seeds of faith and nourish them through utilizing the spiritual gifts enumerated in the New Testament, the Book of Mormon, and the Doctrine and Covenants. Intellectual study of the gospel surely has its own advantages. I spend significant amounts of time in intellectual study. Yet, ultimately, we won’t find lasting answers or peace to our questions using this method. We only find answers and peace by seeking the Savior. While seeking Him, we can ask for ever-increasing faith. Having faith in Christ is specifically listed as a spiritual gift in the scriptures. We can pray for this specific gift to increase our faith and, in turn, increase our peace.

Rabbi Evan Moffic believes uncertainty possesses its own kind of beauty:

Faith is not about answers. We err if we think faith solves our uncertainty. Authentic faith is not about easy answers. Rather, it is about finding the courage and wisdom to live with uncertainty. Faith can help turn uncertainties into blessings. In fact, uncertainty can ultimately sustain and make our faith even stronger. I first recognized this truth during a visit to Venice. The city has magnificent churches. Yet, these churches are built on lagoons. The soil is watery and muddy. How can such shaky ground hold up such extraordinary structures? The tour guide explained the way it works. The churches are built on thousands of wooden poles that move with the tide. Those movements counter-balance one another, keeping the structure high and intact. The very shakiness of the structure keeps it standing. The same is true with faith. The uncertainties we face sustain us. They bring us closer to one another. They bring us closer to God. It is through the uncertainties, the challenges, the crises—what the Psalmist calls the “valley of the shadow”—that we see God is truly with us. Uncertainties also sharpen our vision. They help us refine and grow in faith, separating the wheat from the chaff, the sacred from the mundane. It is not certainty that leads to faith. It is the courage to live with uncertainty. An 18th century rabbi named Nachman of Breslov said, ‘the whole world is a narrow bridge, and the most important part is not to be afraid.’ In other words, life is uncertain. It resembles a rickety bridge. We walk across it in faith: Faith in our ability to do so, faith that the bridge will hold, and faith that God beckons us from the other side“

(The Secret of Living With Uncertainty, On Faith Voices, July 17, 2015.)

I would add that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and its leaders may, at times, resemble (in our own minds) a shaky or rickety bridge. As Church members, we too, will inevitably walk across it in faith.

Our faith will be tried

Plan on it. Author Grant Von Harrison’s observations echo my own experiences:

From the very beginning the pattern followed by the Lord in granting blessings has been: 1) the Lord allows the person seeking the blessing to be tested and tried and 2) once the person humbles him/herself and proves his/her faith by perseverance and sustained faithfulness, the righteous desires are granted. A period of proving, or a trial of faith, is necessary to see if someone who is seeking a special blessing from the Lord will remain faithful in the face of opposition. If a person understands that his/her faith is going to be tried, it gives him/her a greater resolve to be persistent in times of opposition. It is extremely important that you realize that trials of faith are a necessary part of the sanctification process by which we are purified by the Spirit of God. Opposition plays a very important part in this process, for by overcoming opposition and enduring affliction we are, in a very literal sense, purged and made clean. When you endure opposition by serving the Lord to the utmost of your ability—no matter how limited your ability is—the grace of God is sufficient to intervene in your behalf“

(Drawing From the Powers of Heaven, p. 49-50.)

Christmas, 2016 with our grandchildren. Since then, an additional granddaughter and grandson have been added to our family.

I end with this final thought. Surely, Nephi had it all figured out when he said:

For behold, the promises which we have obtained are promises unto us according to the flesh’ wherefore, as it has been shown unto me that many of our children shall perish in the flesh because of unbelief, nevertheless, God will be merciful unto many; and our children shall be restored, that they may come to that which will give them the true knowledge of their Redeemer“

(2 Nephi 10:2).

I can testify that many seeds of my faith have blossomed into a strong belief. And my belief has eventually given way to a knowledge; for instance, my sure knowledge that Jesus Christ is the Savior and Redeemer of the world. And though my knowledge is still not perfect, it is knowledge and no longer faith. Faith precedes and sustains!

Here’s to attaining and sustaining,

Julie